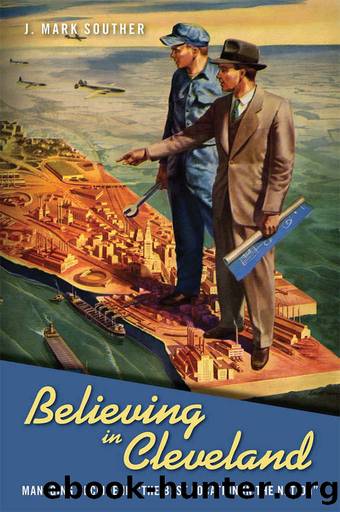

Believing in Cleveland (Urban Life, Landscape and Policy) by J. Mark Souther

Author:J. Mark Souther [Souther, J. Mark]

Language: eng

Format: azw3

Publisher: Temple University Press

Published: 2017-11-03T00:00:00+00:00

The Cleveland Foundationâs Gradual Embrace of Playhouse Square

The Halprin plan certainly appeared capable of creating a unified, appealing downtown. Perhaps because Halprin so skillfully wove together many varied projects with committed advocates and gave attention to the entire corridor between Public Square and Playhouse Square, his plan and the organization charged with carrying it out could take credit for individual successes while remaining aloof from initiatives that did not succeed. For example, the Garden Club of Cleveland, headed by the Plain Dealer publisher-editorâs wife, Iris Vail, adopted the enhancement of Public Square as a cause. Piggybacking on the approaching U.S. bicentennial, the Garden Club held a patriotically themed benefit ball at the Arcade in 1975, netting $175,000 that seeded a less-ambitious plan than Halprinâs for revamping Public Square.56 Likewise, although the Playhouse Square revitalization campaign predated Halprinâs arrival by a few years, its chief advocates, including members of the Junior League, were among the short list of leaders to whom Halprin was introduced in 1973, and he continued to cultivate them during the workshop process. The inclusion of Hadden as a cochair of DCCâs Playhouse Square committee and of Shepardson and other dedicated backers of the theater district revival as committee members was an acknowledgment of the promise of that effort, a way of claiming a connection to it, and an attempt to pull what had started as a grassroots movement into the orbit of the growth coalition.57

As the Cleveland Foundation situated itself more openly and directly within the growth coalition through its sponsorship of Halprinâs plan, its leaders also warmed to the idea of embracing Playhouse Square, but they did so on their own terms. Shepardsonâs Playhouse Square Cabaret showsâespecially Jacques Brel, which closed in the summer of 1975 after a remarkable 522 performances that grossed more than $1.5 million from more than 135,000 attendeesâhad proven that suburbanites would spend an evening downtown if given something fun to do. Yet these shows did little to move the needle in terms of generating the necessary funding to undertake the kind of transformational redevelopment that an increasing number of observers expected and that a much-maligned city seemed to require for improving its image. Even after the commencement of Junior League backing, Shepardson remained accustomed to doing little better than breaking even. Sometimes the only profits his shows netted came from the sale of popcorn, liquor, and concessions. Cleveland Foundation executive director Homer Wadsworth later characterized Playhouse Squareâs backers somewhat dismissively as âa bit naïveâ and their efforts as resembling âcocktail party planning.â58

More than simply a concern about the lack of a solid business footing gave pause to the foundation. There was, Hadden noted, a desire to see something approximating Ghirardelli Square or Bostonâs soon-to-open Faneuil Hall Marketplace, which was garnering considerable national attention as a new model for downtown renewal. It is worth recalling that, as late as 1975, Strawbridgeâs Settlersâ Landing project in the Flats, with its location near Higbeeâs and the planned Tower City Center, still looked more likely to anchor a strong shopping, dining, and entertainment concentration than Playhouse Square.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Africa | Americas |

| Arctic & Antarctica | Asia |

| Australia & Oceania | Europe |

| Middle East | Russia |

| United States | World |

| Ancient Civilizations | Military |

| Historical Study & Educational Resources |

The Dawn of Everything by David Graeber & David Wengrow(1685)

The Bomber Mafia by Malcolm Gladwell(1608)

Facing the Mountain by Daniel James Brown(1541)

Submerged Prehistory by Benjamin Jonathan; & Clive Bonsall & Catriona Pickard & Anders Fischer(1444)

Wandering in Strange Lands by Morgan Jerkins(1406)

Tip Top by Bill James(1400)

Driving While Brown: Sheriff Joe Arpaio Versus the Latino Resistance by Terry Greene Sterling & Jude Joffe-Block(1361)

Red Roulette : An Insider's Story of Wealth, Power, Corruption, and Vengeance in Today's China (9781982156176) by Shum Desmond(1343)

Evil Geniuses: The Unmaking of America: A Recent History by Kurt Andersen(1338)

The Way of Fire and Ice: The Living Tradition of Norse Paganism by Ryan Smith(1322)

American Kompromat by Craig Unger(1298)

It Was All a Lie by Stuart Stevens;(1291)

F*cking History by The Captain(1286)

American Dreams by Unknown(1274)

Treasure Islands: Tax Havens and the Men who Stole the World by Nicholas Shaxson(1251)

Evil Geniuses by Kurt Andersen(1246)

White House Inc. by Dan Alexander(1202)

The First Conspiracy by Brad Meltzer & Josh Mensch(1164)

The Fifteen Biggest Lies about the Economy: And Everything Else the Right Doesn't Want You to Know about Taxes, Jobs, and Corporate America by Joshua Holland(1111)